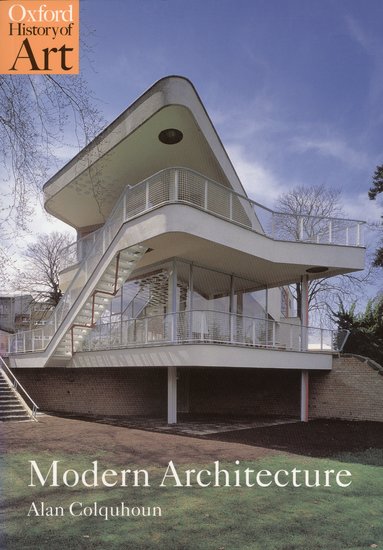

Some good books on architectural topics:

- Alan Colquhon, Modern Architecture (Oxford History of Art

series) - OUP, 2002

An introductory, yet scholarly, account of the development of architectural modernism in the period between the last years of the C19th and World War II. The author presents a masterful synthesis of material. He identifies the path of development of the avant garde architecture designed and actually built in the period and seamlessly weaves this together with a history of the theoretical ideas and trends that informed it. The writing is incredibly concise given the coverage, so makes for a great entry-point to the subject. Generously-sized pictures illustrate well the points made in the text.

A 30-page, no-bullshit guide to the geometric techniques used to construct the basic elements of Gothic architecture: pointed arches, tre/quatre-foils, and rose windows. It is eye-opening to see how simple the straight-edge and compass rules involved are.

- John Grindrod, Concretopia - A Journey Around the Rebuilding of Postwar Britain, Old Street, 2013

This is a book about post-war construction in Britain: the story of how and why development in the UK in roughly the period 1945-1975 took the shape it did. As Grindrod handles it, this turns out to be quite an exciting tale: the early optimism of the wartime generation buffeting the headwinds of post-wartime shortages; some hard-won successes and a number of heavily-felt failures. There are numerous sub-plots which the author disentangles and presents in chapterised form as manageable mini-tales. These, of course, include those of the Festival of Britain and the South Bank, the New Towns, and the notorious experiments with "streets in the sky", together with the occasional collapsing tower block disaster. But Grindrod also brings to light some less well-known stories, such as the period's architecturally pioneering school-building programme, bold private-sector schemes to build entirely new settlements along progressive lines, and shocking, yet now entirely forgotten, corruption scandals involving the out-and-out bribery of politicians by construction bosses in the 1950s and '60s (a nice reminder that the popular notion of that era as a somehow more straightforward time is simply bullshit). The book is written in a conversational, documentary style, anchored by the author's own interviews with the protagonists, bit-part players and end-users (ie residents) of this flurry of construction effort. It also embraces other primary sources such as newspaper articles, journals - not only those of architects but also the likes of Concrete Quarterly - and even developers' brochures. Concretopia is, therefore, not only an entertaining and informative read, but is also a worthy piece of research in its own right.

- Rosemary Hill, God's Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain, Penguin, 2008

The Pugin that emerges from this biography is a likeable fellow. The man sort of bounds his way through the Victorian Age like an energetic dog. He builds up a practice whilst finding the time to write breathless, barely grammatical pamphlets promoting his take on the Gothic Revival - polemics which somehow succeed in making his name and instigating a profound shift in public taste. He gets caught up in (and sometimes knocked about by) the age's strong currents of religious and political sentiment. At one stage, he controversially converts to Catholicism and yet somehow, in that prejudiced time, is allowed to design - which he goes on to do brilliantly - much of the Houses of Parliament, including perhaps the icon of Britain, the Big Ben clock tower. We find him dining with some of the richest men in the land whilst trying to supplement his sometimes precarious income by scavenging the shores of Kent for wrecked treasure. He embraces industrial production techniques to make his medievally-inspired interior design items, which he finds himself showcasing in The Crystal Palace during the Great Exhibition.

Understand this man, one feels, and one could understand the Victorians as whole - those strange, fervent, contradictory people who Built The Modern World. You feel you are starting to obtain both those levels of understanding as you read this beautifully written book. For Hill is a great biographer in that it is not only her immediate subject that she knows inside out, but also the entire milieu in which he operated - not just the subtleties of social rank (that favorite obsession of English writers), but the strange theological debates of the time, the economic realities of the construction industry, and the means by which ideas were then disseminated in the press and through networks of private correspondence. Hence she can explain who was on whose side, what was being debated, where the power and the money lay. And she communicates that knowledge so very deftly: just a tiny bit of background here, a smattering of exposition there - concise and telling. All that is woven seamlessly into truly great storytelling. I read this book years ago, but some of the vignettes - say that of the 4-year old Pugin bossing about luggage handlers as his family boarded a ship - remain more vivid in my mind than a lot of historical fiction I've encountered.

- John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice, First Published 1877, Edited and abridged JG Links 1960, Pallas, 2001

It is hard to explain the appeal of Ruskin's writing. You can't turn to him for self-improving information: he doesn't systematically set out how to date a building or tell a Doric column from an Ionian one - neither

Stones, nor its predecessor

Seven Lamps of Architecture, offered a "Dummies' Guide to Architecture" to the Victorian reading public. Nor did he write amusing travelogues that charm with self-deprecating tales of mishap-filled adventure. He was not a Jerome K Jerome or a Bill Bryson. Indeed, the one thing that anyone who knows anything about Ruskin knows is that he was not a particularly likeable person, although this popular view is probably

somewhat unfair.

So what's so good about Ruskin? I think it is the way that his prose combines that slightly deranged (to modern sensibilities) evangelical energy of the age with an amazing penetrating attention to psychological reality. It is strange - and perhaps even slightly erotic - to be walloped over the head with a delicately calibrated thought experiment. For instance, in arguing that pinnacles are primarily decorative rather than structural elements, Ruskin writes: "[i]f the reader likes to ask any Gothic architect with whom he may happen to be acquainted, to substitute a lump of lead for his pinnacles, he will see by the expression of the face how far he considers the pinnacles decorative members". It's the difference between mere force and pressure: the words are not only forceful but precisely targeted. The effect is stimulating - a bit like receiving a deep massage.

Sure, Ruskin scatters about stirring, sometimes Biblical imagery ("...

like the dim morning light as it faded back among the branches of Eden"). But

Stones of Venice is never highfalutin, because the concern is, ultimately, always with real, immediate psychological mechanisms.

It is always asking "what does this make us feel, and why?", and above all "what can we infer about the thoughts and passions of the people who made it?". It's an attitude that happens to be quite in tune with up-to-date scientific thinking about how the brain works, which posits that we operate

by actively constructing models about how the world works and trying to infer causal mechanisms, rather than merely absorbing information and dumbly responding to it (the point being that it is not just, as one might otherwise think, art critics like Ruskin himself who wonder about how our environment is put together, but that we are all doing this all the time without conscious effort, hence it is plausible that this sort of thinking is relevant to the formation of aesthetic impressions). At any rate, it's an essentially

cognitive approach: architecture as something that happens as immediate, real, tangible thoughts in people's brains, rather than the transmission of obscure concepts over a scale of decades through a disembodied intellectual ether, as if ideas spoke directly to each other without the slightest mediation of human thought. It's the opposite, in other words, of the approach that would write a sentence like "

Architecture finds itself at the mid-point of an ongoing cycle of innovative adaptation – retooling the discipline and adapting the architectural and urban environment to the socio-economic era of post-fordism" - and I think rather more modern.

- Simon Unwin, Analysing Architecture, Routledge, 3rd Edn, 2009

A text evidently designed mainly for architecture students but readable enough to appeal to non-practitioners like myself. The book is arranged thematically, so, for example, there is a section on how architecture may engage with the five senses, a part on proto-typical places ('hearth', 'bed', 'theatre', so on), and a particularly interesting section on what the author describes as "themes in spatial organisation", which abstracts out universal architectural techniques such as the use of parallel walls. Just occasionally it gets a bit platitudinal (eg "Products of architecture combine acceptance of some aspects with change of others. There is, however, no general rule to dictate which accepts are accepted and which should be changed or controlled."), but it is at least mercifully free of jargon. Friendly, non-didactic in tone, the approach is very much 'here are some different ways people have sought to respond to this or that design problem - be inspired, draw your own conclusions' - which works well. Illustrated throughout with the author's own crisp line drawings - a generous average of maybe 2 or 3 per page.

- Clough Williams-Ellis, Architect Errant, Constable, 1971

Autobiography of the man behind

Portmeirion. I found it fascinating, albeit I'm a bit of a Williams-Ellis obsessive. Still, surely the life of a guy who built an entire village at his own expense over several decades, turning it into a popular holiday destination that found international fame with cult '60s TV-show

The Prisoner; could tell anecdotes about hob-nobbing with genuine celebrities such as Bertrand Russell and Frank Lloyd-Wright, fought in WW1; helped establish Snowdonia National Park; was invited to travel to the Soviet Union under Stalin to teach the Soviets about town planning, and lived well into his '90s (he wrote this book in his '80s) dressing like an Edwardian dandy until the last, makes for an interesting tale.

No comments:

Post a Comment